For a graduating senior at Biola, the walk across Metzger stage to receive oneãs diploma can be a blur. Itãs a journey packed with meaning, yet itãs over in just a few seconds. When Dianey Burgos walked across that stage on May 26, however, it was the culmination of a much longer journey. For Burgos ã the first member of her family to graduate from college ã it was the end of a journey that began in East L.A., on a street bordered by gangs on one side and drugs on the other.

Dianey (pronounced DNA) grew up only 14 miles from Biolaãs La Mirada campus, but in many ways it was about as far from Biola as you can get. Few people in Dianeyãs neighborhood make it to a commencement stage of a private university. Dianeyãs mother and father ã first generation immigrants from Mexico ã made it as far as junior high (mom) and second grade (dad).

ãEver since I can remember, my mom told me, ãGo to school, get educated so you can have a career, so you can be better than this,ãã said Dianey, who caught a break in high school when she transferred out of Roosevelt High to Bravo Medical Magnet High School, where everything is oriented toward the goal of going to college.

Dianey had no idea what Biola was before hearing about it from friends and people at her church, who urged her to apply. She visited campus on University Day and wasnãt hugely impressed, but something pressed her to apply anyway.

ãI know it was God leading me here,ã said Dianey, who found out only after sheãd been accepted that several friends had been praying for her to choose Biola.

Soon Dianeyãs mind was made up: She was coming to Biola. Her parents took more convincing. Even with scholarships and financial aid, sending their daughter to a private university on a janitorãs income was hard to envision. The only way it could work was if Dianey didnãt stay in the dorms on campus but instead commuted to campus via public transportation.

It was a sacrifice Dianey was willing to make.

A Long Dayãs Journey

At 5 a.m. each morning, five days a week for her entire freshman year, Dianeyãs dad dropped her off at Union Station in downtown L.A. on his way to work. From there, Dianey ã 17 years old, alone, without a cell phone ã took three separate trains to Norwalk, and then a bus to Rosecrans and Biola avenues, from where she would swiftly walk to campus in order to make her 8 a.m. classes. L.A. traffic and public transportation being what it is, she was almost always late. Her professors never knew why. Few of her friends did either. Dianey was quiet about her commuting situation.

At night, Dianey repeated the arduous buses-and-trains journey, though it took even longer than in the morning. If her last class ended at 4:30 p.m., it would be around 8 p.m. sometimes before Dianey got home, leaving her only a couple of hours to do homework and sleep before it was time to repeat the relentless cycle.

She used the time on the buses and trains to do homework, read her Bible and chat with those around her. Numerous conversations were sparked when people noticed Dianeyãs reading material, and she was able to share the gospel with some.

She also did a lot of praying. As a young girl, frequently surrounded by strange men coming home from work, constant prayer was a lifesaver.

There were moments when the commute felt like an unfair burden. One afternoon at the end of her first semester, Dianey remembers standing at the bus station on Rosecrans, waiting for a bus that was very late.

ããI hate this. Why am I doing this?ãã she remembers thinking. ãIt was embarrassing. I saw friends drive by, and I thought, ãWhy donãt I have that? My friends are already home, safe, having dinner. And Iãm standing here alone, hungry, with a bunch of homework to do, waiting for a bus that is late.ãã

The commute was a struggle, but for Dianey, Biola was worth it. She pressed on and made the rigorous commute each day during her freshman year, rising every morning earlier than when many Biola students go to bed.

ãThe crazy thing is she didnãt think this was abnormal,ã said Tamra Newman, Dianeyãs admissions counselor and mentor for three years. ãShe was just pursuing an education, and would take whatever lengths she needed to.ã

Struggling to Stay

Though she was able to live in the dorms starting sophomore year, Dianey faced other challenges as a student at Biola. As a commuter and minority on a mostly white campus, it was sometimes hard to relate to the typical Biolan.

ãI was intimidated, especially when people spoke up and knew more than me,ã she said. ãEspecially in my Bible classes.ã

Having gone to a Spanish-speaking church her whole life, Dianey had to learn Bible stories in English for the first time at Biola. She had to learn how to pray in English. She was unfamiliar with the term ãmissions trip,ã and didnãt quite get the typical Biola humor.

And then there were the financial struggles. Dianey couldnãt afford a meal plan her freshman year; she relied on friends to swipe her into the Caf or bring her extra food. Her dad collected cans and recyclables so Dianey could afford all the books she needed. Her aunt gave her a laptop sophomore year, the same year she got her first cell phone.

Finding loans and paying tuition was a semester-to-semester struggle, but God was faithful and Dianey made it through Biola with a debt-load less than what it could have been. Her junior year as a resident assistant, Dianey had an income and was able to help her parents out a bit. Senior year she resolved to not take any loans out at all. Her aunt surprised her by covering the tuition balance for fall semester, and then ã to Dianeyãs complete surprise ã her own parents told her they had saved up money so that they could pay in full for her last semester of college.

As her parents told her they wanted to pay for her last semester, tears streamed down Dianeyãs face.

ãI was so thankful,ã she said. ãI knew how hard it was for them to save up that much money. It was so special.ã

For her parents, Griselda and Filemon Burgos, Dianeyãs education took a lot of sacrifice, but it was worth it.

ãWe thank God for opening a door for our daughter to reach her goal,ã they wrote in an email. ãWe understand and believe that it is all about believing in the Almighty.ã

Back to the City

May 26, 2012, was the first day Dianeyãs parents spent time on Biolaãs campus, aside from dropping her off at the dorms. They were intimidated on campus. It was difficult to relate to the world of Biola, but they were there to cheer on her daughter as she graduated. Dianeyãs graduation was a success as much for them as for her.

ãItãs not just me who made it,ã said Dianey. ãItãs all of us who made it.ã

Sheãd come a long way since that morning four years prior when her dad dropped her off at Union Station for her first day of college. In four years, Dianey had gone from being a commuter who kept to herself to a widely known and respected leader on campus. Sheãd developed a tight-knit community through B.E.A.T. (Biolaãs Ethnic Advancement Team) and had grown a lot through her experiences as an R.A. in Sigma, a mentor to others and a worship leader.

ãI saw her transform from a student with a passion to sing to a strong worship leader,ã

said Newman, who worked with Dianey in B.E.A.T. ãShe is someone that I continually call on to lead worship in the Biola community for Spanish and English worship or simply for a diverse worship experience.ã

A highlight of Dianeyãs Biola experience was when she was invited to sing in chapel during Latino Heritage Month. She chose the song ãCristo, Yo Te Amo,ã which means ãChrist, I Love You.ã

ãLeading Biola students in singing that song in Spanish was probably one of the best days of my life,ã she said. ãAfter that I just felt like, ãIãve done my work.ãã

But there is work still to be done.

Graduating as a sociology major, Dianey leaves Biola to return to her community in East L.A. to pursue a career in social work. Her education at Biola didnãt make her ashamed of ãthe hoodã she calls home; it equipped her to return as a beacon of light.

The Only Thing we Have to Fear

Itãs takes a pretty fearless person to take six train and four bus rides every day, alone, to get to college. For Dianey, overcoming fear is one of the big lessons she takes away from her time at Biola; she learned the value of vulnerability and putting her needs out there, allowing herself to be known and grown by others. Itãs a concept she takes with her back to East L.A.

ãIn my L.A. community I see a lot of fear ã a fear of expressing needs or asking for help. I want to tell my community, ãThere is help for you; thereãs always a way.ãã

It takes courage to change oneãs position in life, but itãs possible. Dianey knows this better than most, and so do her parents. As they watched their daughter receive her diploma from President Barry H. Corey, they saw the fruits of their sacrifice but also the tangibility of grace and blessings given by the God of hope.

For many years Dianeyãs parents have worked to bring peace and the love of Christ to their street in East L.A. Her father ministers to the men ã the gangbangers, the drug dealers, anyone; her mother ministers to the women.

ãNow itãs my turn,ã says Dianey. ãWhat can I do for the youth? I want to offer them hope.ã

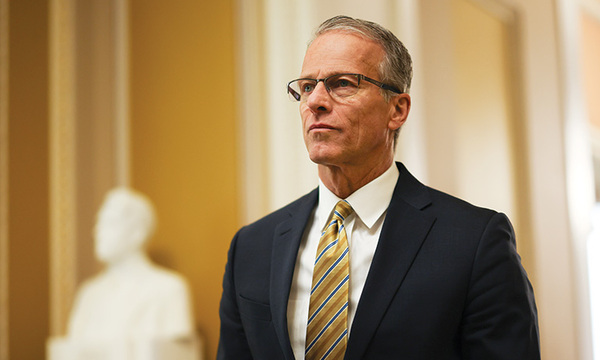

Kira Williams contributed to the reporting of this feature. Photos by Mike Villa.

¤Öêüâºòñ

¤Öêüâºòñ